I started learning a language just before the pandemic began. If you hadn’t already sussed it, I’m a bit of a word nerd. I like knowing words and where they come from – and how that same thought can be represented in another way. When you make those translations while speaking, they need to be rapid and seamless. Then you can hear the sameness of the thought and the slight differences in the translation. In effect, switching the language transposes the thought.

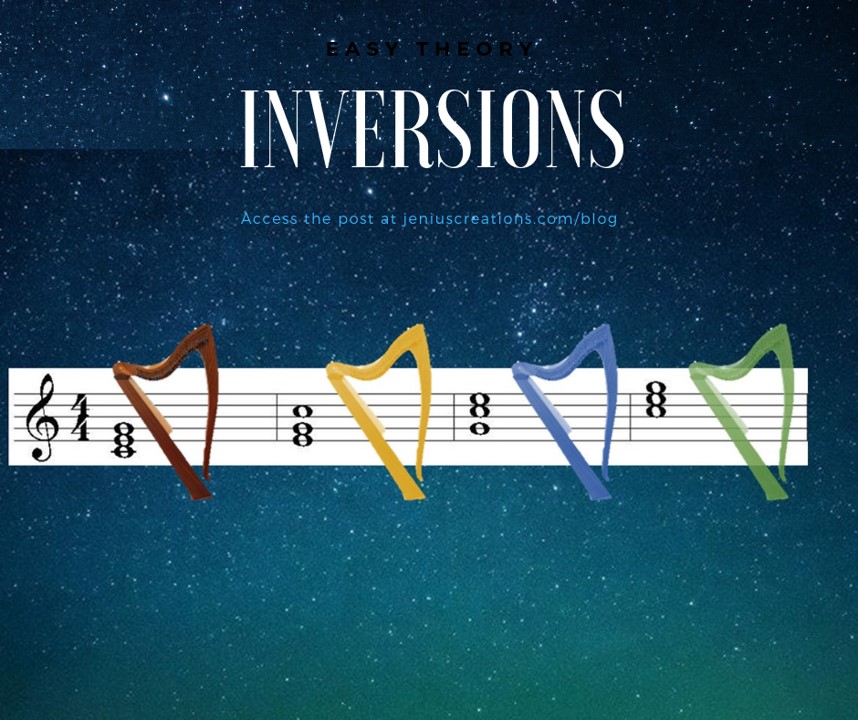

When we’re playing, sometimes we need to do the same thing and transpose to a new key. Why? Well, we can transpose to play with someone else (e.g., all the Bb instruments), or to support a singer, or to fit a tune on your harp (so you can use all of it without “running out of strings” or because you just like the sound of it better in a different key.

Are you thinking “ugh”?

Transposing is a very useful skill that will serve you well. It’s a good workout for your brain. It’s good for building flexibility in your playing too. It’s also intimidating to many – after all, if you’ve not learned how or just haven’t practiced, it can leaving you feeling be uncomfortable and embarrassed.

Before I go on, let’s start with – what is transposing? It’s a big, scary word for moving from one key to another. For us as harpers, it’s actually not too scary and certainly less work than for some other instruments. We just have to move to the new lever/pedal setting and everything else stays the same – the fingering, the spacing. In fact, the only things that change after resetting the lever/pedal are the look of your finger on the string and the pitches.

I won’t lie to you – when you start trying to transpose, it’s challenging (that’s my fancy way of saying it’s harder than lots of other things). Your poor brain is going to try to “translate” every note, one at a time. Often, at the beginning, you might just be guessing. But like everything else we do, taking a moment to think will help us become better and get faster sooner. All of this will also help you become more facile with theory (or it will come to you sooner if you already know your theory and how to apply it).

The hard way – that so many people go through – is to identify the relationship of the key you know the tune in and the key you’re transposing to. But don’t fall for thinking that a small move is easier than a bigger one. It’s easy to think that moving from C to D (for instance) will be uncomplicated – after all you just have to move up a string. But that’s why it’s hard – you have to second guess every note, keeping track of which is the “old note” and which is the “new note”. If the new key is farther away, then you have to “translate” every note. If you move from C to A, each note is now a 6th above (or 2 below the old right note) so you have two opportunities to second guess – did you do the math right (in one direction) and the close problem (in the other direction) – ugh.

Do it the hard way often enough and you’ll be glad stop and think first! Because you already know what you need – the intervals are what matters. If you know what the intervals sound like (yup, ear training!), you’ll be even closer to making the transposition easily. The fingering and patterns will help solidify the move when you transpose.

While you can think about all this when you’re transposing, imagine how far ahead you’d be if, when you learned the tune, you’d been thinking about the intervals and relationships, rather than just the note names and sequences! Same thing with the harmonies. Rather than memorizing the chord names, think about their place in the scale and the chord progression. If you know I, VI, V – you’re on the way. Learning the chord progression as a set of relationships will make it so much easier to remember.

If all that makes sense to you – now practice doing it. Take some well-loved, well learned, often played tune, and put it in another key. Keep at it – the more you practice doing it, the easier it will become.

If all the above is so many words that don’t make sense to you, don’t worry. They will. They just might need to percolate. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also try it. The practice is what will help get it into your head.

Before you say, “yeah, yeah, whatever” – think about your next harp circle or session. There will be some tune you love that you want to play along with everyone, but they’re all playing it in the key of Qb mijor, so you’re left either sitting there wishing you were playing OR you’ll employ your new skill and tuck in! What tune do you love that everyone else plays in some other key? How are you going to transpose it? Let me know in the comments!