There is a lot of music out there. Probably millions of tunes through the ages. Last week we talked about the joys of learning by ear, which are many.

But for all the lovely tunes available out there, if you’re going to learn them by ear, you have to find a source from which to learn. And that’s not always a possibility. You might live in the hinterlands. Your SpotiTube could be clogged. You might have eaten your Apple tunes. It might be that no one has thought to record the tune. Or possibly that no one remembers it?

And this is where writing music down is so helpful. I’m sure even the most amazing of harper bards of old would have been hard pressed to learn, know, and use all the tunes available – then or now. So, I hope we can agree that writing the music down is a helpful thing – if only to try to keep track of (at least a little corner of) the universe of tunes. Ah, Paper.

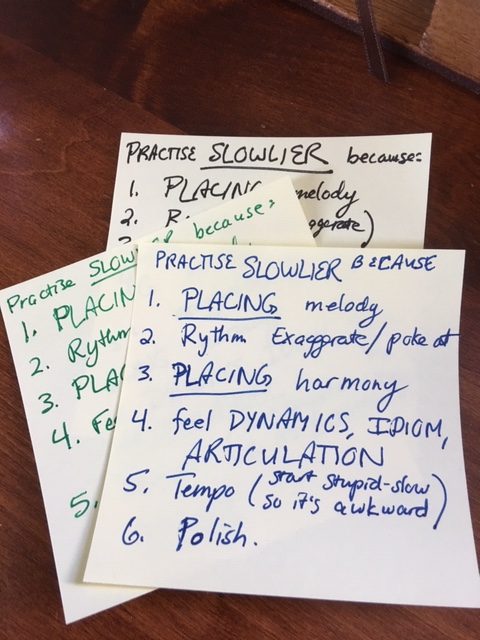

This is true for any type of music. Don’t be fooled – even the hallowed classical music is not meant to be played strictly as written. Mozart made his stock and trade writing and performing his music. And when he performed – his shtick was improvisation – that is not found in the writing! And he is just one example.

This is true for any type of music. Don’t be fooled – even the hallowed classical music is not meant to be played strictly as written. Mozart made his stock and trade writing and performing his music. And when he performed – his shtick was improvisation – that is not found in the writing! And he is just one example.

There is an easy trap in believing that the printed music is better than aurally transmitted tunes. It absolves one of all need to really internalize the music. And unquestioning devotion to the dots (the notes) excuses us from putting in the effort to make the music our own.

Written music is simply a tool. It can serve as a memory aid or it can act as a framework from which to pull the music. But it isn’t unassailable, nor does it require strict adherence. Ick.

As a tool it has myriad uses including keeping a record of a tune for later use, holding a tune for others not present when it’s being played, and for memory keeping. Writing it down allows one to capture of ideas, snippets, measures (and other stuff), even if they’re not “interesting” just now (not everything is popular all the time – but eventually the wheel turns).

Like any tool, the written music has limitations. For instance, it can’t capture all the feeling or the interestingness with which individual players imbue a tune. It will, with time, lose parts of its meaning, leaving future generations to conjecture (ok, just guess) what was meant by what was written, how it was played and what it was for. Don’t think that’s true? Look at the Song of Seikilos (found on a grave marker) – I’m pretty sure they thought they were capturing that for posterity*….

Which highlights another limitation – the written music can’t really capture the “à la mode” or “dépêche mode” (like how I did that?!) for the tune – you’ll get the bones but not the juicy cultural meat – you have to research (or guess) what the tune might have meant. You can have dogmatic discussions all day long but, in the end, you’re going to play it the way you hear it in your head – because that’s all you can do with the dots.

But most importantly, the dots can serve another function – that is helpful in the concrete, rather than in the abstract. This visual representation of the music makes music more accessible to those who are not good at hearing (don’t process auditory information well). When you look at the dots you have another avenue to getting at the tune – the relationships between the notes are spaced in the plane of the staff rather than over time (as in auditory representation). Some people can better understand the relationships of pitch and rhythm when looking at them than when listening to them.

Perhaps the most important point is that there is no “better” – learning the tune by ear has many benefits and some drawbacks. Learning from the paper also has many benefits and some drawbacks. These benefits and drawbacks maybe different, but they point to a potential strength – using both!

Using both auditory learning (learning by ear) and visual learning (learning by reading) may help you learn even more faster and more better (yes, I meant to say it that way). Just like learning by ear, the more you read, the better you’ll get at it.

Ah paper, a wonderful tool!

* If you’re not familiar with the Song of the Seikilos, it is the oldest surviving musical composition, believed to be from the 1st or 2nd century. The composition was found on an ancient Greek grave marker https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/oldest-song-in-the-world/