Poetic License

Hopefully you’re still working on those dynamics exercises. I say hopefully because they are challenging and if they are new to you, you probably aren’t all the way through in just a few weeks. And even if they are not new to you, the exercises I shared aren’t easy. They definitely aren’t a set of “once and done” exercises either!

I think I made a compelling case for why you would want to work on your dynamics. But just in case I wasn’t blunt enough, here I go again. We talked about music being a means of communication – you are telling a story. Not every story needs to be a soporiphic bed-time story, so we need dynamics to help carry the tale through its ups and downs.

Just like storytellers, narrators, or actors vary their delivery – we want to vary our own, in aid of the story we’re telling. We use those variations to help move our listener along with us. But we don’t want to just gormlessly vary our loudness – we need to be a bit more subtle!

Another thing we can easily hear storytellers, narrators, and actors do is varying the pacing that they achieve through their breathing. We call it phrasing (heck, they might too, what do I know?). And we can use dynamic changes to support the shape of the phrases on top of the breathing we are already infusing into the phrase shaping. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about let’s do a preparatory exercise before we go to the harp. Pull out your favorite poems! Let’s start with a limerick to warm up. These are goofy and sing-song-y and you know exactly how to read them aloud: da-da-da–da-da-da–da-DA, da-Da-da–da-da-da-da-DU, da-da-da-da-DA–, da-da-da–da-DU, da-da-da–da-da-da–DA! Really dig into the cadence. Read them repeatedly, emphasizing the sign-song nature of the rhyme. When you’ve reread a few times and really have the rhythm going, focus on how you need to breathe to support that cadence. Once that’s not a struggle, you’re ready to use that breathing to support varying the loudness with which you say each syllable. Notice how you make a curve shape with your breathing and loudness like this:

Once you feel like you understand this concept, move into other (more mature?) poetry – Browning? Hughes? Shakespear? Yeats? Choose your favorite (or pick the one you’ve never actually read (but would never admit to having skipped!)) and start reading aloud. Find the cadence, shape the phrases. Listen to the ebb and flow of your voice and its volume. Once you’re established in reading the poem, shift the loudnesses – if you need to, mark the page, and try emphasizing the typically unemphasized syllables and shout them out while only whispering the usually emphasized. How does that change how you hear the poem?

Now, let’s turn the idea inside out and let’s mess with the poem! Read a poem out loud in a goofy way – read Byron as if it was a limerick or read the silliest limerick you can find as if it was a sonnet. Add an extra beat to iambic pentameter and make it jiggy! Do silly things to your reading to find different ways to present the cadence and rhythm of the poem and the breath and dynamics to get there.

After some excursing (both “serious” and “silly”), go back to your original interpretation and notice: has your breathing changed? How is your loudness varying? Have you had any changes now that you’ve thought of the words in different presentations?

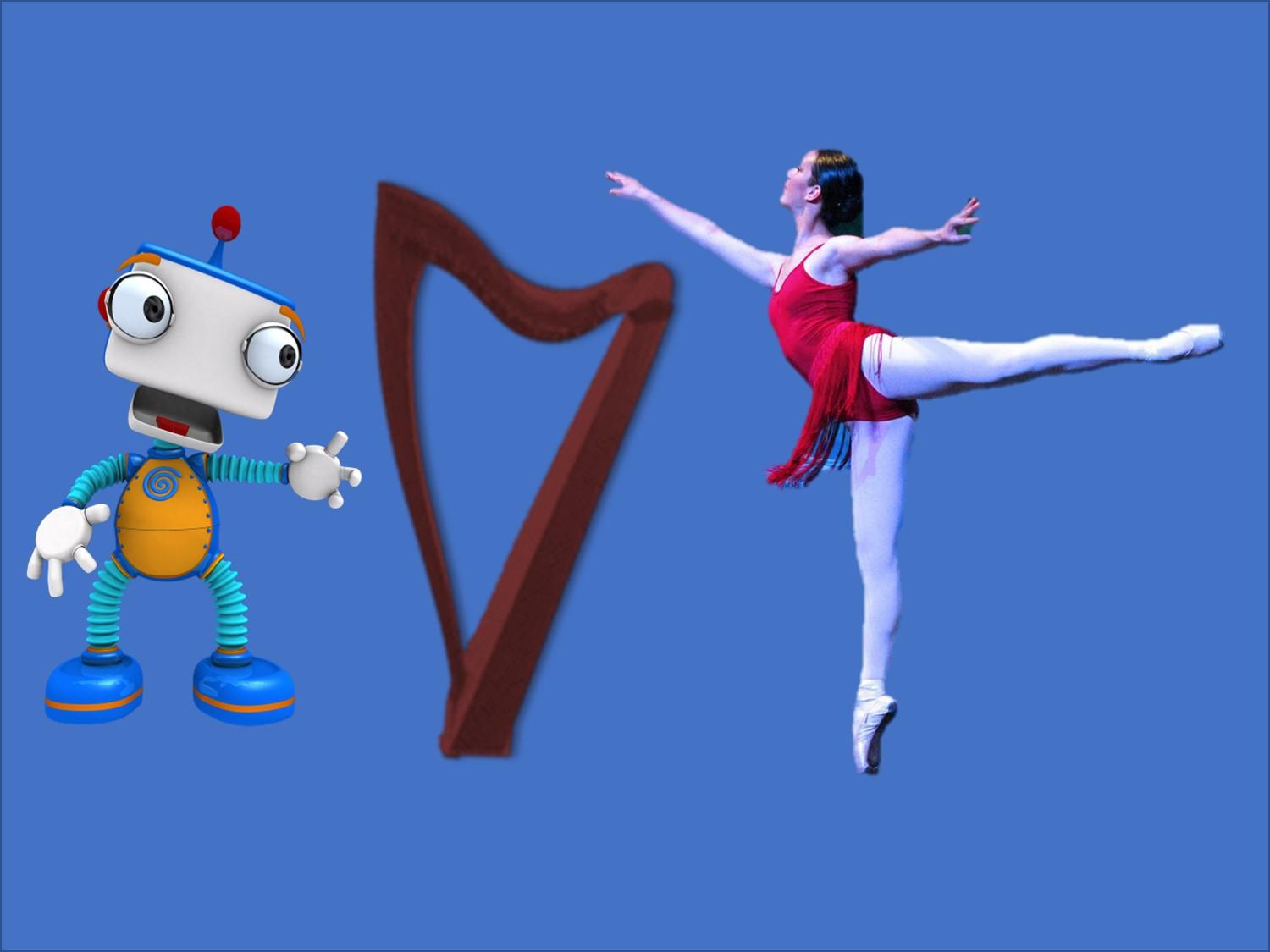

Now, go to your harp and do this same (sort of) thing – shape the phrases (like the graphic above) as you want to present the music. Now, make it into a “limerick”! For instance, play a 4/4 lament as if it were Katie Bairdie (or a 3/4 march as if it’s a jig). Take it from hushed to explosive! Then, go the other way and play a typically lively tune as a lament. Just mess around with it and see how you can shape the phrase to tell your different stories – and watch how the breathing and shape of the phrase change and how your volume control helps support that.

Clearly this is another set of exercises that aren’t “once and done” – you can do these exercises repeatedly and over time to explore all the corners of phrasing. Remember too that:

1. These are exercises. There’s no wrong. There is only exploration.

2. It is your story to tell. There is no wrong, only your interpretation.

3. They’re called dynamics for a reason! You can play the same sort of dynamic repeatedly and every time you play a tune. Or you can play a different set of dynamics each time you play. There is no wrong. It’s your story to tell your way.

4. Things change. Sometimes a tune always makes you feel the same things, no matter how many times you play it. Sometimes the tune leaves you feeling different, depending on how you experience it that day. There is no wrong – tell the story you hear.

I know this set of ideas is really different from what you might normally think of as harp playing, but give it a try and let me know what happens. What do you learn? What happens next (for you)? How do you think differently about your playing now? Can’t wait to hear your thoughts in the comments!